NIST

| Industry: | Government |

| Founded: | 1901 |

| Headquarters: | Gaithersburg, Maryland |

| Country: | USA |

| Employees: | Approximately 3,400 (2021) |

| Website: | https://www.nist.gov/ |

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is a physical sciences laboratory and non-regulatory agency. As part of the United States Department of Commerce, its mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's laboratory programs include nanotechnology, engineering, information technology, neutron research, material measurement, and physical measurement. The institute was founded on March 3, 1901, as the National Bureau of Standards, and it became NIST in 1988.[1]

Computer Security Resource Center

The Computer Security Resource Center (CSRC) has two subdivisions, the CSD and the ACD.[2]

Computer Security Division

The CSD is focused on information systems and specializes in cryptographic technologies; secure systems and applications; security components and mechanisms; security engineering and risk management; and security testing, validation, and measurement.

Applied Cybersecurity Division

The ACD specializes in Cybersecurity and Data Privacy applications, hosts the National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence (NCCoE), and runs the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE).

NCCoE

The NCCoE's mission: to expand the use of a secure cyber infrastructure that inspires technological innovation and fosters economic growth.[3]

The NCCoE's strategy: to accelerate the business sector's adoption of standards-based security technology by consulting with IT practitioners to identify the most pressing issues, generating technical descriptions of those problems, matching solutions with NIST standards and best practices, making the problem descriptions as broadly applicable as possible, and inviting technology vendors to collaborate on product modules of end-to-end example solutions.[4]

NCCoE Collaboratorations:[5]

- IT users report problems.

- Integrators implement NCCoE reference designs and provide feedback to the NCCoE to help make the references easier to deploy.

- Vendors in the NCCoE labs with researchers, contributing expertise, hardware, and software to the development of the reference design for a specific problem.

- Reference design users deploy example solutions and provide feedback to validate/improve them.

- Other government agencies work with NCCoE through the National Cybersecurity Federally Funded Research and Development Center (NCF).[6]

- Core partners provide hardware, software, knowledge, and personnel. The current group of partners includes:[7]

NCCoE Projects:[8]

| * 5G Security | * Patching the Enterprise |

| * Adversarial Machine Learning | * Post-Quantum Cryptography |

| * Data Security | * Supply Chain Assurance |

| * Derived PIV Credentials | * TLS Server Certificate Management |

| * Internet of Things (IoT) | * Trusted Geolocation in the Cloud |

| * Mobile Device Security | * Zero Trust Architecture |

NICE

SP 800 Series

NIST’s Special Publication (SP) 800 series shares computer security information. Created in 1990, the series reports on the Information Technology Laboratory’s research, guidelines, and collaborations with industry, government, and academic organizations.[9]

SP 800-37

The “Guide for Applying the Risk Management Framework to Federal Information Systems” promotes near real-time risk management, encourages the use of automation, integrates information security, emphasizes the selection, implementation, assessment, and overall monitoring of information security controls, links risk management at the information systems level to risks at the organizational level, and establishes responsibility and accountability for security controls.[10]

NIST SP 800-37 Rev. 2 (RMF 2.0) aka "Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy" superseded RMF 1.0 (above) on December 20, 2019, providing guidelines for applying the RMF to information systems and organizations.[11]

Significance of RMF 2.0:

- the first NIST publication to include full integration of privacy risk management into the existing information security risk management processes;

- direct references to the Cybersecurity Framework, i.e., implementing RMF 2.0 helps achieve Framework outcomes;

- the Prepare step achieves more effective, efficient, and cost-effective security and privacy risk management processes. Previously part of SP 800-18, -30, -39, -47, and -160, this step institutionalizes organizational- and system-level communication facilitation by offering organizations a single, focal resource and methodology;

- catalyst to organization-wide identification of common controls and the development of tailored control baselines;

- reduces the complexity of the IT infrastructure; and

- provides methods to identify, prioritize and focus resources based on risk/value analysis.[12]

SP 800-171

Cybersecurity Framework

Version 1.0

History

In February 2013, recognizing the national and economic security of the United States depends on the reliable function of critical infrastructure, President Barak Obama issued Executive Order 13636, "Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity," ordering NIST to work with stakeholders to develop a voluntary framework based on existing standards, guidelines, and practices for reducing cyber-risks to Critical Infrastructure. On December 18, 2014, the Cybersecurity Enhancement Act of 2014 (CEA) authorized the Department of Commerce, through NIST, to develop voluntary standards to reduce cyber-risks to critical infrastructure.[13] The law also ordered the Office of Science and Technology Policy to develop a federal cybersecurity research and development plan. Section 502 required the Director of NIST to ensure interagency coordination toward the development of international technical standards for IT security and transmit to Congress a plan.

Framework Development

February 26, 2013: RFI to Develop a Framework to Improve Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity - February 12, 2014: Framework 1.0 Publication.

- One year after the release of Executive Order 13636 and following one RFI, five workshops, and one RFC, NIST released version 1.0 of the Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity.[14]

Components

The resulting Cybersecurity Framework consists of voluntary standards, guidelines, and practices for promoting critical infrastructure protection. The Cybersecurity Framework consists of three main components: the Core, Implementation Tiers, and Profiles.[15]

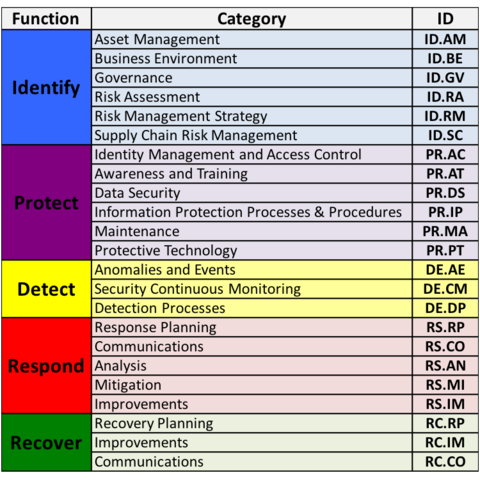

Core

The core is a set of desired cybersecurity activities and outcomes organized into Categories and aligned to Informative References.

Tiers

The tiers do not describe maturity levels; rather, they describe the degree to which an organization’s cybersecurity risk management practices exhibit the characteristics defined in the Framework. It is up to each organization to decide its target tier. The Tiers range from "partial" to "adaptive," reflecting an increasing degree of rigor, integration among cybersecurity risk decisions, and information sharing between the organization and external parties.[16]

Profiles

Profiles refer to the alignment between each organization's requirements and objectives, risk appetite, and resources and the desired outcomes of the Framework. The profile system is meant to help organizations identify opportunities for improving their cybersecurity posture by comparing their current profiles with their target profiles.

C3

The Department of Homeland Security's Critical Infrastructure Cyber Community (C3) Voluntary Program helps owners and operators align their organizations with the framework and manage their cyber risks.

Version 1.1

On April 16, 2018, NIST released the updates to version 1.0, which:[17]

- Clarified that compliance terminology,

- Added Section on Self-Assessing Cybersecurity Risk,

- Expanded Section 3.3 on Communicating how to use Cyber Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM),

- Added the Section 3.4 Buying Decisions, which highlights understanding the risk associated with commercial off-the-shelf products and services,

- Added Cyber SCRM criteria to the Tiers,

- Added Supply Chain Risk Management Category to the Framework Core,

- Refined the language of the Access Control Category to better account for authentication, authorization, and identity proofing,

- Explained the relationship between Tiers and Profiles,

- Integrated Framework considerations within organizational risk management programs, and

- Included a subcategory for coordinated vulnerability disclosure lifecycle.

References

- ↑ About NIST

- ↑ About CSRC, NIST

- ↑ NCCOE Strategy

- ↑ NCCOE Strategy

- ↑ Stakeholders, NCCoE

- ↑ NCF Fact Sheet, NCCoE

- ↑ Partners, NCCoE

- ↑ Building Blocks, NCCoE

- ↑ SP 800, NIST

- ↑ About SP 800-37, Flank

- ↑ ITL Bulletin, NIST

- ↑ RMF 2.0 Bulletin pg. 4

- ↑ CEA, IT Law Wiki

- ↑ History of Framework Creation

- ↑ Framework Components, NIST

- ↑ Framework Components, NIST

- ↑ Description of CF Version 1.1